Treasures from Andalusia

In 2013, my colleague Mike Sabbagh and I were studying in the post-graduate course in "Typography & language" in ESAD Amiens, working on the creation of Latin-Arabic typefaces. Wishing to learn more about the richness of the Arabic-Muslim legacy, we made a one-week study trip in Andalusia. This is a summary of this trip, rich in discoveries.

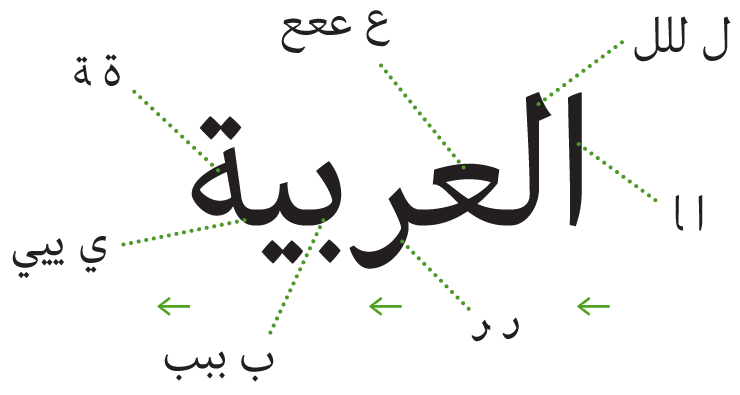

First, according to me, it seems important to briefly explain the operation of the Arabic script. It uses an alphabet of 29 letters, it is devoid of capitals, and common names and proper names are not particularly differentiated. It is a cursive writing which is drawn from right to the left. Letters may be up to four different forms depending on their position in the word: isolated, initial, medial or final. That said, six letters have only two forms (isolated and final); they are not associated with the next letter.

The word Al-Arabiya: the Arabic language

So as to create my Latin-Arabic typeface Batutah, I drew from various sources like Internet, books, museums and archives such as the University of Reading (England). I find it important to have a diversified research of references as Paul Shaw advises in his article "Ten Simple Rules for Researching Letterforms". All these researches helped me in my work but I wanted to go further up to meet history in Andalusia. For nearly eight centuries, this region of southern Spain was under Muslim rule (711-1492); we find this architectural footprint in many buildings such as castles, palaces and mosques. We will talk about the Alhambra in Granada and the Great Mosque of Cordoba. What's better than sites listed by UNESCO to study the beauty and richness of Arabic calligraphy?

Generalife gardens

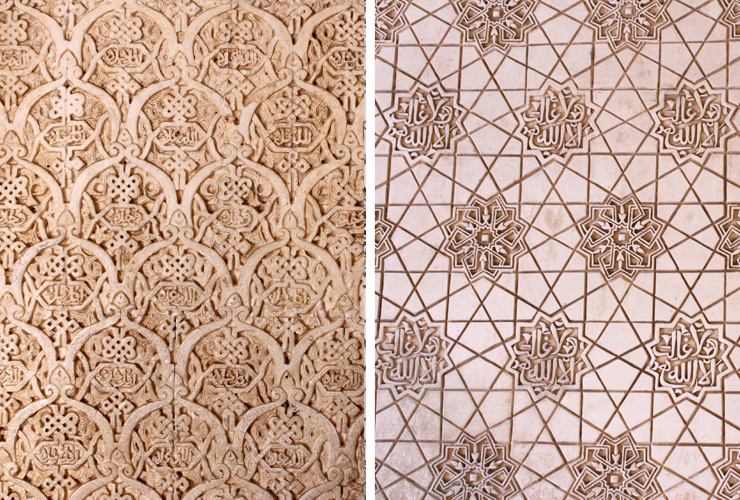

The first stage of our trip was the Alhambra in Granada. It is so named in reference to the Arabic word Al-Hmrā ', "red" because of the color of the hills of the region. The first buildings began in the Nasrid dynasty in 1238 and continued during the next generations. The Alhambra is therefore not only a fortress but a palace complex composed of gardens and outbuildings where many people lived. Palaces are profusely decorated, often from floor to roof, without any empty space. Inscriptions used to show both the power of the sovereign and his devotion.

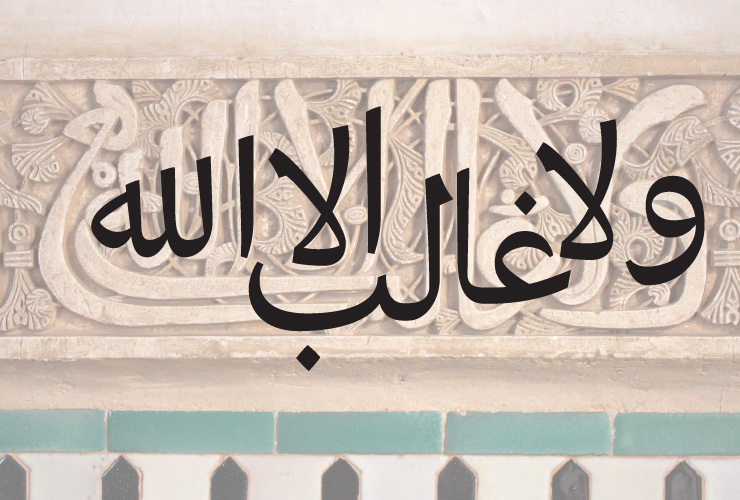

"There is no victor but Allah"; transposition in modern Arabic

Above, the sentence becomes pattern while repeating itself along a wall frieze. Like many inscriptions of Alhambra, it has been made in stucco from wooden moulds in order to be repeated a lot of times. This moulding is similar to the Maghribi style, characteristic of North Africa and Spain. Appeared around the 10th century, it is calligraphed with a smooth rounded reed pen which gives round endings and a lot less strong contrast than in other styles. There is often some letters elongation passing under the base line. There are many variations of this style across regions and over time.

Prayer room of the Mosque of Cordoba

Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba is a building with a stunning story. In 584, the Visigoths built on the site of the Roman Temple, the Church of St. Vincent Martyr. In 786 Abd al-Rahman Ist launched the construction of a mosque that will be continued by his successors. At the end of the Cordoba Caliphate, the mosque spread over 850 columns on 23.000 m2. After the Reconquista of 1236, a church and a cathedral were built in the middle of the old mosque. This story, full of upheavals, offers to the visitors a unique example where Umayyad of Spain style and the European Renaissance and Baroque styles mixes.

Exemples of mixes from these two cultures

Gate decorated with floral patterns and calligraphy in Kufic style (blue and red bands)

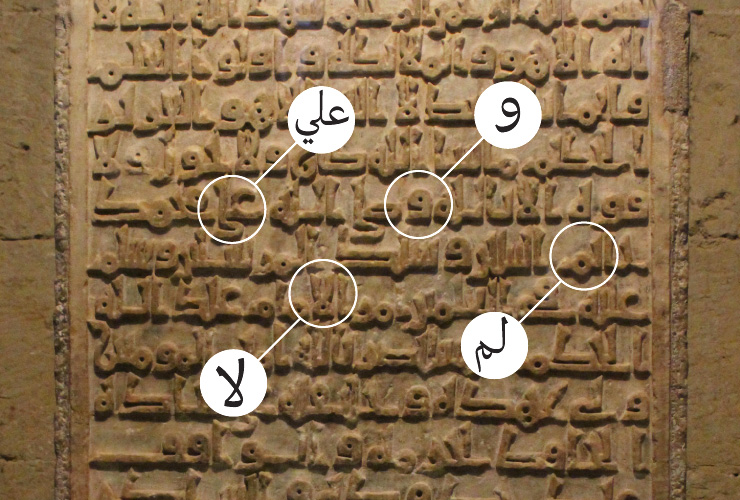

While the walls of the Alhambra are covered in a style resembling to the Maghribi with curves and round endings; in the Mosque of Cordoba, it is different. Here, inscriptions that we found are in the Kufic style, a much more dense and angular shape with quite high ascenders and a fairly geometric appearance. This style was born around the 7th century near the city of Kufa in Iraq and has continued under the Umayyad dynasty and decline around the 13th century. Again, many variations of this style exist.

First stone of a building outside the mosque ; transposition in modern Arabic

Obviously, this Andalusian trip brought me a lot as a graphic and type designer. This trip enabeled me to better understand the richness of Islamic art whether patterns or calligraphy. These achievements dating back no more than 1000 years are still a huge source of inspiration. Whether in a traditional or innovative view, it deserves that we give it time and interest. I invite all designers to swap, from time to time, their computers against a camera and a flight ticket. Have a nice trip to all.

By Thierry Fétiveau – August, 2014. All rights reserved.

Ten Simple Rules for Researching Letterforms